In the dawn of personal computing, Digger, released in 1983 by Windmill Software, stands alone as a rare gem. Combining arcade-style excitement with strategic nuance, this early IBM-compatible game presented an addictive challenge wrapped within colorful charm and delightful sound.

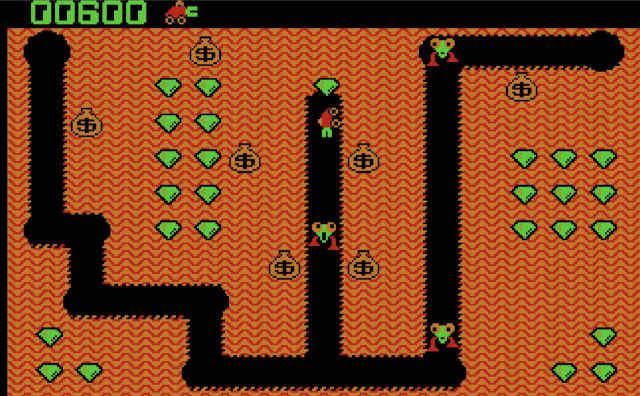

The premise involved navigating mazelike tunnels, gathering emeralds, avoiding or eliminating enemies, and hoarding shimmering gold. Simple objectives concealed layers of complexity, demanding timing, planning, and adaptability. Each level presented tighter mazes and faster adversaries, pushing reflexes while also rewarding clever pathfinding.

Visuals employed CGA graphics, now primitive but once dazzling. Four-color palettes painted a vibrant underground world. Every sprite, crude by modern standards, brimmed with personality. The protagonist, a small mining vehicle with blinking eyes, conveyed urgency as danger approached. Opposing creatures each moved distinctively, some floating, others marching, all bent on pursuit or destruction.

Sound effects offered more than ambience. Familiar melodies accompanied play, most notably a chirpy rendition of Popcorn, punctuating action with cheerful rhythm. These audio cues, despite limitations, enhanced immersion. Background silence would occasionally yield sudden jingles, signaling power-ups or impending threats, lending tension or relief depending on situation.

Gameplay introduced a sense of inertia. Unlike modern platformers, momentum dictated turns and stops, encouraging foresight. Dropping boulders onto enemies required patience, as any miscalculation might end a promising run. Sometimes escape depended on exploiting behavior patterns rather than brute force.

Victory conditions encouraged exploration. Treasure accumulation was vital, but mere survival became equally significant. As speed increased, one misstep often led to doom. Lives felt valuable, forcing calculated risk rather than reckless digging.

Technically, Digger was a marvel. Designed specifically for early DOS systems, it ran smoothly without requiring advanced hardware. Compatibility proved impressive given era constraints. Keyboard responsiveness remained consistent, preserving fairness despite rising difficulty.

What truly separated Digger from contemporary offerings was its atmosphere. A sense of mischief pervaded each session. Baddies weren’t merely obstacles; they appeared mischievous, playful even. Traps felt earned rather than cruel. Progression carried emotional weight—pride when conquering a level, amusement when falling to absurd fate.

Furthermore, the game’s replay value deserves praise. No two attempts unfolded identically. Procedural elements, while subtle, ensured variation. Each restart taught something new. Losing rarely felt frustrating because knowledge gained provided motivation. Mastery required dedication, but rewards exceeded expectation.

Cultural impact, though perhaps underappreciated today, cannot be denied. Digger inspired numerous clones, ports, and remakes. Its influence persisted long after floppy disks vanished. Fans continue creating tributes, adapting code for modern systems, demonstrating enduring affection.